Everyone will be sharing opinions about D&D Next today and for the foreseeable future. I wanted to do something a little different and focus on just one thing: the math behind the Advantage and Disadvantage mechanic.

For those who haven’t read the playtest material yet, if you have Advantage for a die roll, you get to roll twice and take the better result (kind of like the Avenger in 4th Edition). If you have Disadvantage, you have to roll twice and take the worse result.

In reading through the rules, I noticed that being blinded gives you disadvantage for your attacks, while being prone gives you the same -2 to your attack that you would get in 4th Edition. So what’s the impact of disadvantage? Is it similar to a -2?

Averages

My first thought was, what’s the average of 2d20 keeping the highest (advantage), and what’s the average of 2d20 keeping the lowest (disadvantage)? I know that the average of a single d20 roll is 10.5, so knowing the average of advantage or disadvantage should tell me whether it’s equivalent to +/-2, +/-3 or what, right?

I decided to simulate this by having Excel roll a whole bunch of dice (over a million pairs of d20 rolls) and then taking some averages. For those fellow Excel geeks out there, my d20 roll formula is: =ROUNDUP(20*RAND(), 0). I generated two columns of these, then a column that was the maximum of the two results (=MAX(A2, B2)) for advantage and one that was the minimum (=MIN(A2, B2)) for disadvantage.

I got a result of about 13.83 for a roll with advantage and 7.18 with disadvantage. I later learned that the precise values are 13.825 and 7.175. Comparing this to the 10.5 average you get for a single d20, advantage adds 3.325 to the average roll and disadvantage subtracts 3.325.

Done! Right?

It’s not all about the averages

However, as my fellow EN Worlders soon pointed out, this isn’t the most useful way to look at things. In D&D, what you care about is your chance of success or failure on a die roll. And when you change the distribution of results from a uniform d20 roll (equal 5% probability of every number from 1 to 20) to the maximum or minimum of 2d20, the impact is not the same as a straight plus or minus to a d20 roll.

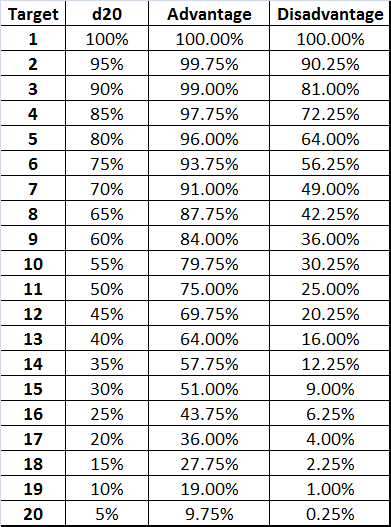

The most useful way I’ve found to look at this is with the following table. The first column shows you the target number you need to roll on the die in order to succeed. (Note that if you need an 18 to hit but you have +6 to hit, then the target number on the die is a 12.) The second column shows the percentage of time you’ll get that result or better on a single d20 roll. The third column shows how often you’ll get your number with advantage, and the fourth shows the same for disadvantage.

What does it all mean?

Let’s take an example from the table. Assume you need to roll an 11 to succeed. With a straight d20, you have a 50% chance of success. With advantage, this goes up to 75%. That’s the equivalent of a +5 bonus to the roll, since you would also have a 75% chance of success if you only needed a 6 or better on a single d20. Pretty impressive!

On the flip side for the target of 11, disadvantage means you only have a 25% chance of success, equivalent to a -5 penalty to the roll (when you need a 16 or better on a d20, you also have a 25% chance of success).

So does that mean advantage/disadvantage is equivalent to +/- 5? Not all the time. In fact, it’s only that big when you need exactly an 11 on the die.

Let’s say you need a 15 on the die to succeed. With a single d20, you’ll only get this 30% of the time. With advantage, you’ll get it 51% of the time – about the same as you would get an 11 or better on a single d20. So advantage in this case is worth about a +4. Disadvantage, similarly, is about a -4: You only succeed 9% of the time with disadvantage, which is about the same as a single d20 with a target of 19.

At the extremes, advantage makes the least difference. If you need a natural 20 to hit, that’s only going to happen 5% of the time normally. Advantage ups your chance to 9.75% – equivalent to getting a +1. Disadvantage takes you chance down to 0.25%, or 1 in 400. That’s the chance of rolling back to back crits – not a common occurrence. But in terms of a modifier, it’s not much different from giving you a -1 to your roll when you need a 20 – it’s just about impossible.

In reality

Most of the time, D&D tends to set things up so that you need somewhere between a 7 and a 14 to succeed on a task unless it’s trivially easy or ridiculously hard. If you look at the percent success in the d20 column for those rows, then find the equivalent percent success in the Advantage column, you’ll see that this is usually similar to getting a +4 to +5 bonus to the roll. Disadvantage is exactly the same in the opposite direction.

So there you have it. For target die rolls that are reasonably close to the middle of the range, advantage or disadvantage is about the same as having a plus or minus 4 or 5 to your die roll. It’s pretty powerful – much more powerful than the +2 for combat advantage that you get in 4th Edition.

Note that I haven’t factored in the additional chance of a critical hit with advantage, since I don’t really care about damage per round or anything like that. Suffice it to say that your chance of critting with advantage is 9.75% instead of 5%, and you can do the rest from there.

– Michael the OnlineDM

@ClayCrucible on Twitter

Nice analysis. The new 2D20 advantage/disadvantage mechanic sounds like an interesting experiment. I can’t wait to try it out.

Well then… Guess I don’t need to put up my article on the analysis. Agree with your conclusions… Excellent article :).

Slainte,

-Loonook.

I got the same results on my analysis as well, and I also am glad that someone posted theirs so I don’t have to.

There’s an analytic formula for the probabilities of the max or min of pairs of dice of a given side, no need for simulation. If the die type has D sides and X is the number you want to roll, then

Pr(X) = (X^2 – (X-1)^2)/D^2

which simplifies to

Pr(X) = (2X-1)/D^2

If you want a justification, draw a square with D rows and columns and label rows and columns with the die roll on a given die. There will be D^2 boxes. Each box has probability 1/D^2 of occurring. Inside each box write the max of the two rows. If you count them up you’ll see that they follow the rule I just gave. Another way to think about it is that the number of boxes that have a value of X or smaller is X^2, so by taking X^2 – (X-1)^2 you are counting the number of boxes that have an X in them. Dividing by D^2 once again normalizes for the total number of boxes.

(It is worth your time to do this for, say D = 6 to get a feel for the process.)

Beyond that, max or min has the benefit of preserving the original range of the D20, so you can’t exceed the numbers given, while giving the effective bonuses listed in the article. That is, it’s about +4 or so for the way D&D tends to be calibrated, but you can’t actually exceed the performance you could expect without advantage.

The formula for mins works the same basic way but the probabilities are reversed, as can be seen from the table above. (This formula generalizes to trios, quads, etc., by using cubes, quartics, etc.)

Thanks for the math! I did come to understand this as I worked on it; I only shared the results of my simulation because that was my own starting point and I thought it was an interesting story.

Yes, I didn’t mean to knock simulations. They’re often useful ways to explore things, but if you have an analytic solution it’s even better.

Okay, I’m clearly not getting it with regard to Pr(X) = (2X-1)/D^2 …. Does this mean that, if I want to roll 2 d6 and get a 6, then I calculate it like so: Pr(6) = (2*6-1)/6*2? This gives me 11/36, which seems to be right … I would expect to get at least one 6, 11 times out of 36 throws.

Here’s where I am missing something (it may be I don’t understand the use of the carrot – D^2).

If I want to know my chance of getting at least a 5 on 2 throws of a d6, my 6*6 chart shows I can expect that at least 20 times out of 36, but the formula above looks like:

Pr(X) = (2X-1)/D^2

Pr(5) = (2*5-1)/36, or 9/36 so clearly I’m not getting something.

This isn’t an attempt to sharpshoot your math; I’m certain there’s something I don’t get here. Can you help me understand?

The formula is not the probability of getting at least a number, it’s the probability of getting exactly that number.

D^2 is D squared. So if D = 6 then you have 6^2 = 36 possibilities.

I’d also not want to write the max of 2D6 as 2 D6 because that’s much too close to the standard 2D6, which is for the sum of 2D6.

How about max(2,D6) or something like that?

Oh one meta-point:

When working with probabilities it’s frequently much easier to determine

Pr(X <= x)

that is the cumulative probability than the probability of a particular value x directly. So if you want to know Pr(X = x) just use the fact that

Pr(X = x) = Pr(X <= x) – Pr(X <= x-1)

(This is only true for discrete variables that are scored as integers, such as dice.)

Pingback: Weekly Roundup: D&D Next Playtest Is Here Edition | Roving Band of Misfits

Pingback: My Thoughts on DnDNext after 1 Session @ RPG MUSINGS

Pingback: My Thoughts on DnDNext after 1 Session @ RPG MUSINGS

Pingback: Links of the Week: May 28, 2012 | Keith Davies — In My Campaign - Keith's thoughts on RPG design and play.

You analysis made for extremely interesting reading, however you failed to take into account one of the most important aspects of this mechanic: rolling more dice = more fun!

Heck yeah! Rolling more dice is awesome, I agree.

If you’re rolling max(D20,D20) for 20 giant rats and thus have to roll 40 dice in 20 die chunks, I’d really have to say the answer is… no, not so much. Lots of die rolling takes time and grind time is most definitely not fun for everyone sitting there and waiting.

While I like the system, I wish there was some way to have “minor (dis)advantage”: the equivalent to the +2. I guess I should just give +2.

Yep. If you look at the rules for being prone, you’ll see that the -2 to attack still exists.

A.k.a. Circumstance bonus?

While it may be new to D&D, this mechanic is hardly new at all. Savage Worlds uses this for all rolls by the PCs, for instance. But, at least WotC is developing a 21st century game rather and 20th century one now.

I don’t recall anyone particularly playing up the novelty of this mechanic in this article. But I don’t see any need to belittle the company here.

It is not the article, it is the folks who only play d20/D& X that need to understand there are other games doing very modern methodologies. I was actually being sincere that wotc is thinking in both the past and the future.

Roll D20 and pick the better of the two is already in 4E. Lots of powers do that and an entire class, the Avenger, is built around it.

You’re right, that a max mechanic has been done for a while. Savage Worlds did it, but as I recall Deadlands (Savage World’s ancestor) did it before. Another game with a max mechanic is Blue Planet.

Pingback: To Roll or Not To Roll | Working As Unintended

A friend sent me a link to your article, but I thought the graphed data set was also really interesting. Not only is Advantage better more often, but it is SO much better than +2. Anyway, the graph is also good for those who like pictures (like me!). This is a fun problem!

https://docs.google.com/open?id=0BzSg1t-UrV8pelpCRXRwNWUwYUU

(Crossposted to both articles on this analysis! I am SO happy to see math in the world!)

Pingback: Roleplayers Chronicle » Under the Hood – Odds of Excitement

Pingback: Reading the Entrails: What the Mearls Reddit Says About Next (Part 2) « The Evil GM

Pingback: Combat Speed in D&D Next | The Id DM

Pingback: The (Dis)Advantaged « Jack's Toolbox

Pingback: 5 Minute Work Day » Advantage & 4e Skills

Great article! Thank you for writing it.

For some reason, you didn’t seem to get a pingback when I wrote an analysis/extension of this article even though I followed the link within my article back to this page – something that I have only just noticed. It’s probably not especially relevant anymore, but here’s a link to my article: http://www.campaignmastery.com/blog/implications-of-ddnext-advantage/

Pingback: Meta Thursday: Advantage and Disadvantage in D&D NextAdventure-A-Week

Pingback: Additive Advantage: My First 5th Edition House Rule? | Ali Rolls For Damage

Pingback: D&D 5e: Probabilities for Advantage and Disadvantage « Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science

Pingback: Rubare alla 5ed per dare ai poveri master: il vantaggio dove lo metto? – Cronache del gatto sul fuoco

Pingback: Our Favorite D&D Stats Sites (So Far!) | Ludus Ludorum

Thanks, this is great! The table is especially handy. The new mechanic gives 5e a really distinctive flavor over all the previous editions, and remains simple to use.

The easiest way to put it: Advantage makes rolling under an 11 uncommon (25%). Disadvantage makes rolling above a 10 uncommon (25%).

Pingback: prendere le idee migliori di D&D5ed per altri gdr d20

Hi. I just wanted to point out that there is no average roll on one die; this is the most significant feature of a single die system like d20. You mention a couple of times the “average” roll on 1d20 being 10.5 — it’s not the average, but rather the mean. Your simulation results are still apt, but if you’re posting about dice probability, you should be making the distinction and not referring to average result in a range of equal probabilities.

Andrew – To be clear, when ordinary people use the word “average” they are referring to the arithmetic mean. That’s the usage I’m following here.

So, in case anyone is confused, the “average” result of 10.5 that I’m talking about here is the mean, not any other measure of central tendency.

Honestly, I doubt if anyone was confused by this. But there you go.

Pingback: Game Theory: Shooting Into Melee | Basement Dwellers Gaming Club

Pingback: Additive Advantage [5th Edition House Rule] | Roll for Damage

Pingback: Indie Tabletop RPGs: They Exist, They’re Cheap…and You’ll Love Them | LOS ANGELES: 2019

All I know is … dice are not as predictable as the math dictates. I have seen 3 rolls of 1 in a row on a D20. I have also seen 3 rolls of 20 in a row on a D20. I have also seen someone not roll over a 6 all night long. The shape and weight of the dice are also a big factor. Just my 2 cents and opinion … I have been playing since 1980 so I’ve seen a thing or 2.

I’d say the dice are pretty much exactly as predictable as the math dictates. The problem is that we as humans are pretty terrible as recognizing randomness.

Random doesn’t mean that small batches of rolls (a couple of dozen over the course of an evening) will match neatly to the expected distribution; you’ll get random stretches where someone barely rolls above a 6 all night or where someone seems to get 15+ again and again. That’s the law of small numbers for you!

Of course, your point about the specific dice is correct, too. Sometimes dice get unbalanced and have a bias toward rolling certain numbers. That’s a different problem. But streaks of results that look different from what you would expect from randomness are usually random. Over the course of hundreds or thousands of rolls, the results tend to look like what you would expect, but not necessarily over the course of 20 or 30 rolls.

Actually it’s not the math that’s wrong, it’s people’s assumptions about what the math says. Probability is way more “streaky” than people think. However, many folks believe in the “law of small numbers”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasty_generalization

They (us, it’s all of us) get very bothered by such small patterns. We also notice and remember such streaks and forget the vastly more common, utterly ordinary outcomes.

You’re also right that D20s aren’t as even as one might like. There have been demonstrations to this effect. The old Zocchi Gamescience dice were the best, if you trimmed off the flash that was on them. See:

https://www.awesomedice.com/blog/353/d20-dice-randomness-test-chessex-vs-gamescience/

Finally, rolling technique actually matters. Give those dice a good shake to ensure that there’s no dependence on prior rolls!

Pingback: Friday Knight News – Gaming Edition: 1-JUN-2012 | Gamerati

All of the points made in the article is why i absolutely LOVE the advantage optional rules.

You didn’t have to do a random simulation of millions of dice-rolls. You could use the probability formulas that Criman wrote about, OR just do a computer simulation of the 400 pairs of possible rolls (20×20), each equally likely, have the computer make a decision of which die is the largest (pick either one in a tie), and add up the results and divide by 400 to get the average roll of 13.825 for Advantage.

A very important fact is that rolling with Advantage is not exactly the same as getting a +4 or +5. Low rolls 5 or below are not eliminated, they just get rarer.

Pingback: Morgenstern Revisited: Babble & Bat's Hearing - Hudspeth Games

Pingback: 5e Dodge: A Quick Guide to the Dodge Action - 5E Guru