Update: In my next post, I talk about how I fixed this particular problem for Alchemy Bazaar.

My current primary board game design project, Alchemy Bazaar, has been under development for about six months. I’ve personally conducted over 30 full playtest sessions, and I’ve had at least five other groups elsewhere conduct blind playtests. It’s been exhibited at a local convention, local game stores, at board game Meetups and elsewhere.

Throughout Alchemy Bazaar’s development, I’ve been taking careful notes of what works and what doesn’t. I’ve been especially looking for places where the game can be simplified (which I’ve written about before).

I’ve also had a keen eye on balance. This is a game with a wide variety of alchemical shops, formula cards and action cards. Many times, I’ve tweaked one of these that seemed overpowered or underpowered to bring it in line with the others.

Each playtest gave me fewer and fewer of these power level tweaks to make. I was approaching balance across the board. Success?

Well, as the game was becoming more balanced, it was becoming less fun.

This was brought into stark relief for me when my friend Nate, who lives in Seattle, agreed to try a blind playtest with his group there. His group is made up of pretty hardcore gamers, and when Nate called to talk to me about his experience, the news wasn’t good.

Now, part of the problem was a misunderstanding of the rules, and I’ve since clarified the rulebook so that this won’t happen again. But the main problem is that the players felt like their choices weren’t meaningful. If all of the shops were about as good as one another and the same was true for the formulas and actions, then every turn would be about the same as every other..

Alchemy Bazaar had become too balanced.

Nate had a hard time putting this into words, and it was fortunate that he was going to be visiting me in Colorado just a few weeks after this playtest in Seattle. When he was here in person, we were able to sit down and talk through things. Eventually I hit on this question of whether the game might be overbalanced, and he agreed that yes, that was it exactly.

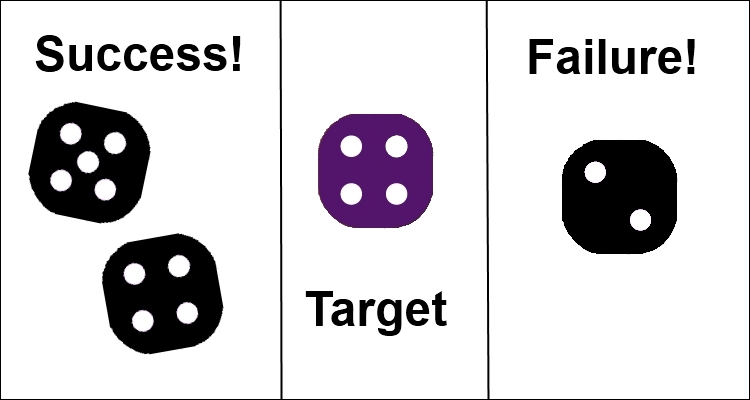

Nate used to work as a designer on Magic: The Gathering, and he pointed out that this was a lesson Magic designers had to learn, too. It helps to explain why the existence of mana screw is actually good for the game; if you never have mana screw, you won’t have that sublime joy and excitement of curving out perfectly.

Look at any game that has great success; chances are it’s not perfectly balanced. I don’t mean that players have unequal chances of winning at the start; that’s a bad kind of imbalance, in my opinion. I mean that there are some options that are more powerful than others, and players will likely be vying over these and excited when they get them.

A great game will have more situational variety in power level. By that, I mean that some options will be really powerful in certain situations and less powerful in others. That’s a wonderful thing to have in games.

But if you balance your game to the point where every choice is about as good as every other choice, you’ve overbalanced. Choices feel meaningless at that point, which is the death knell for any game.

Make sure your game has some intentional imbalance. Even though this means players will sometimes be disappointed by getting a less-powerful option, this is worth it for the excitement of getting that awesome choice at just the right time. Game design is an art, not just a science; don’t forget that!

Michael Iachini, Clay Crucible Games

P.S. My first game, Chaos & Alchemy, is going to be on Kickstarter from Game Salute very, very soon. It has an awesome amount of fun imbalance, I promise. 🙂